“How happy I am to be able to wander among bushes and herbs, under trees and over rocks; no man can love the country as I do. Woods, trees and rocks send back an echo that man longs to hear”.

With these words, recorded for ever in a letter to his friend Therese Malfatti, Beethoven famously declared his love for nature and the landscape around his adopted city of Vienna. An even more explicit outpouring came in the form of his Pastoral Symphony, which will be performed at the Proms on 21 July. For all its obvious appeal, it is easy to forget that Beethoven’s 6th Symphony continued the tradition that began with his second, that of restlessly moving the form , indeed the concept, of the symphony forward.

In the Pastoral there are many innovations we take for granted today. So many, in fact that they add up to a gentle revolution in symphonic thinking. Premiered on the same night as his more overtly radical fifth, the two make a perfect pairing. Whereas the fifth symphony was – uniquely at the time - built around a single, simple musical motif, the sixth is built around a single non-musical idea – the countryside.

He gave each movement its own title beginning with the unequivocal Awakening of cheerful feelings on arrival in the country. Then comes Scene by the brook, with its depictions of landscape, water and of cuckoo, quail and nightingale; followed by a Merry gathering of country folk. The programmatic nature of the symphony is emphasised by the inclusion of a dramatic extra movement depicting a sudden and fearsome summer thunder storm, followed in Happy and grateful feelings after the storm by a perfect simulation of that calm, balmy atmosphere that often follows.

Half a century later, Berlioz was gushing in his enthusiasm for the symphony and the images it conjured: “The shepherds begin to move about nonchalantly in the fields; their pipes can be heard from a distance and close-by. Exquisite sounds caress you like the scented morning breeze. A flight or rather swarms of twittering birds pass overhead, and the atmosphere occasionally feels laden with mists. Heavy clouds come to hide the sun, then suddenly they scatter and let floods of dazzling light fall straight down on the fields and the woods.” And all this from just the first movement. His descriptions of the other four – the Pastoral set a precedent in its five movements – are equally pictorial.

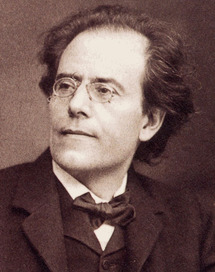

Around a century later, Mahler was to incorporate pastoral episodes in many of his symphonies, often as fragments or themes borrowed from his song cycles. His Songs of a Wayfarer, settings of his own texts, are liberal in their references to birds, and flowers and in celebrating the beauty of the world

With these words, recorded for ever in a letter to his friend Therese Malfatti, Beethoven famously declared his love for nature and the landscape around his adopted city of Vienna. An even more explicit outpouring came in the form of his Pastoral Symphony, which will be performed at the Proms on 21 July. For all its obvious appeal, it is easy to forget that Beethoven’s 6th Symphony continued the tradition that began with his second, that of restlessly moving the form , indeed the concept, of the symphony forward.

In the Pastoral there are many innovations we take for granted today. So many, in fact that they add up to a gentle revolution in symphonic thinking. Premiered on the same night as his more overtly radical fifth, the two make a perfect pairing. Whereas the fifth symphony was – uniquely at the time - built around a single, simple musical motif, the sixth is built around a single non-musical idea – the countryside.

He gave each movement its own title beginning with the unequivocal Awakening of cheerful feelings on arrival in the country. Then comes Scene by the brook, with its depictions of landscape, water and of cuckoo, quail and nightingale; followed by a Merry gathering of country folk. The programmatic nature of the symphony is emphasised by the inclusion of a dramatic extra movement depicting a sudden and fearsome summer thunder storm, followed in Happy and grateful feelings after the storm by a perfect simulation of that calm, balmy atmosphere that often follows.

Half a century later, Berlioz was gushing in his enthusiasm for the symphony and the images it conjured: “The shepherds begin to move about nonchalantly in the fields; their pipes can be heard from a distance and close-by. Exquisite sounds caress you like the scented morning breeze. A flight or rather swarms of twittering birds pass overhead, and the atmosphere occasionally feels laden with mists. Heavy clouds come to hide the sun, then suddenly they scatter and let floods of dazzling light fall straight down on the fields and the woods.” And all this from just the first movement. His descriptions of the other four – the Pastoral set a precedent in its five movements – are equally pictorial.

Around a century later, Mahler was to incorporate pastoral episodes in many of his symphonies, often as fragments or themes borrowed from his song cycles. His Songs of a Wayfarer, settings of his own texts, are liberal in their references to birds, and flowers and in celebrating the beauty of the world

Mahler’s first symphony, which will be performed on 4 September, opens with a movement that seems to be some kind of subconscious response to Beethoven’s Pastoral. The two works have several features in common, notably the use of folk-like tunes (Mahler uses a theme borrowed from the second of the Songs of a Wayfarer) and birdsong-like motifs. Strikingly, both composers wrote explicit instructions in the score to imitate particular birds – quail and nightingale in the Pastoral and the cuckoo in both. Both cuckoos are scored for clarinets, but Mahler’s choice of interval seems wrong – Beethoven correctly has the familiar descending major third, while Mahler’s cuckoo sings the wider interval of a fourth. Can Mahler have got it wrong? He did, after all, choose to do his composing in the countryside, usually in a hut by a lake or in the forest (he had three such huts at different times). He could hardly have mis-heard, or mis-represented such a well-known sound. Perhaps he was particularly struck by an individual with an abnormal call, or maybe he just decided the music needed a fourth. In any case, like Beethoven, he wanted to be sure to get exactly the right attack, degree of legato playing and of staccato in the second note: all characteristic details that make the difference between a cuckoo call and merely two notes on the clarinet. They are all features that could be notated, but both composers decided that a written instruction would be the best way to make the perfect call.

Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending gets its umpteenth Proms outing on 13 August. The archetypal English Pastoral rhapsody, written by a composer linked inextricably with the English folk-song movement and idyllic representations of the Edwardian countryside. Yet RVW was arguably less pastorally-inclined than our other three composers. Country born and bred, at the earliest opportunity he moved to London. He wrote a Pastoral Symphony (his third) that was not particularly evocative of the countryside, nor intended to be. The majority of his output is not remotely pastoral, and many of the folk tunes he borrowed were used as material in decidedly non-folksy pieces. But unquestionably, when he chose to write truly pastoral music – The Lark Ascending, In the Fen Country, the Norfolk Rhapsodies - he excelled, and since such works are performed, recorded and broadcast more often than all his other work combined, he will be associated for ever with what Elisabeth Lutyens famously called “cow pat music”.

Raasay

Raasay My final pastoral composer may seem like a surprising choice at first. Born in the (then) industrial town of Accrington in Lancashire eighty years ago, Harrison Birtwistle has been consistent in his preoccupations throughout his career. Greek mythology, ritual, melancholy and procession figure large in his output. But his first acknowledged piece, written when he was about fifteen, was the Oockooing Bird, the manuscript of which still exists; indeed the piece is available on CD. In this 80th birthday year, the Proms features Sir Harri in five concerts, one of which, on 6 September, is devoted to him alone.

When we launched this site I devoted a page to Birtwistle the lepidoperist. His childhood interest in moths, and his desire in later life to use their decline as a metaphor for wider loss resulted in Moth Requiem at last year’s proms. Here is a videoed conversation in which he refers to the importance of birdsong as a template for many contemporary composers’ styles.

In contrast to Vaughan Williams, Birtwistle has chosen rural locations in which to live. While based in Paris he had a rural retreat, and in the UK the remote island of Raasay or the more gentle rurality of Wiltshire, where he now lives, is where he finds the tranquillity in which to work. It is no surprise that landscape is another favourite subject. Invariably, landscape, or rural life, or birds for example, are viewed through another lens. They serve as subjects in, or backdrops to, explorations of ritual or myth; or, as in Night’s Black Bird (30 July), melancholy.

Several works have the word pastoral in their titles or subtitles: a mechanical pastoral (the opera Yan, Tan, Tethera); stark pastoral and white pastoral (two of his Duets for Storab, the last pieces he wrote during his eight years on Raasay) and so on. While his contemporaries were turning their backs on the Pastoral, Birtwistle seems to have reinvented it.

Laurence Rose

When we launched this site I devoted a page to Birtwistle the lepidoperist. His childhood interest in moths, and his desire in later life to use their decline as a metaphor for wider loss resulted in Moth Requiem at last year’s proms. Here is a videoed conversation in which he refers to the importance of birdsong as a template for many contemporary composers’ styles.

In contrast to Vaughan Williams, Birtwistle has chosen rural locations in which to live. While based in Paris he had a rural retreat, and in the UK the remote island of Raasay or the more gentle rurality of Wiltshire, where he now lives, is where he finds the tranquillity in which to work. It is no surprise that landscape is another favourite subject. Invariably, landscape, or rural life, or birds for example, are viewed through another lens. They serve as subjects in, or backdrops to, explorations of ritual or myth; or, as in Night’s Black Bird (30 July), melancholy.

Several works have the word pastoral in their titles or subtitles: a mechanical pastoral (the opera Yan, Tan, Tethera); stark pastoral and white pastoral (two of his Duets for Storab, the last pieces he wrote during his eight years on Raasay) and so on. While his contemporaries were turning their backs on the Pastoral, Birtwistle seems to have reinvented it.

Laurence Rose

RSS Feed

RSS Feed