NATURAL LIGHT has moved

Thank you for supporting NATURAL LIGHT over the years - please visit our new home!

NATURAL LIGHT has movedThis website has merged with our sister site The Long Spring. Both founded and edited by the writer and conservationist Laurence Rose, their combined features can be found at www.laurencerose.co.uk The new website remains devoted to the natural environment and conservation, and the creative community that is inspired by them. Blogs, essays and news about these subjects, and past, current and future projects and collaborations can be found there, and archive material from this website will also be viewable from there.

Thank you for supporting NATURAL LIGHT over the years - please visit our new home!

2 Comments

...some news about NATURAL LIGHT

NATURAL LIGHT editor Laurence Rose will be taking part in the People's Walk for Wildlife in London on 22 September - see you there?

We're gathering at Hyde Park at 10am. The event itself starts with Infotainment at 12, then we set off at 1pm, walking for an hour to Richmond Terrace. Chris Packham, the walk's organiser, describes the event as a Walk for the Missing Millions: the countless animal and plants that should grace our green spaces in towns and in the countryside, but which have been lost during decades of intensification, mismanagement and impoverishment of the land. People will assemble from all over the country in solidarity for wildlife. PLEASE JOIN US. Click on the video below, for more inspiration!  Photo by Laurence Rose Photo by Laurence Rose

In other news, it is four years since we launched NATURAL LIGHT, a website dedicated to the natural world, and artists who are inspired by it. Starting on the weekend of the Walk for Wildlife, NATURAL LIGHT and its sister website The Long Spring will become a single new website run by author and conservationist Laurence Rose. The new site will bring together the features of both under one roof: as Laurence says, "examining the joints between nature, culture and conservation."

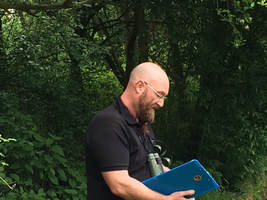

For launch details, follow Laurence on twitter @LaurenceR_write Nine poems inspired by one rare bird Steve Ely by Laurence Rose Steve Ely by Laurence Rose “Over there behind those trees is the most extensive area of scrap metal yards in Europe” said Steve Ely, poet, academic and birdwatcher, to remind us that Carlton Marsh, Cudworth, despite appearances, is an authentic piece of post-industrial real estate. That’s important because what drew us there, some fifteen or so of us, was the willow tit, a bird described by Steve as "nowadays a bird of old colliery sites, dismantled railways and canals." We were on the first of the season’s poetry walks run by the Ted Hughes Project (South Yorkshire). It was also the launch of Zi-Zi Taah Taah Taah, Steve’s single-poet, single-species pamphlet, dedicated to the bird he first encountered in 1979 (an encounter memorialised in one of the nine poems, titled, therefore, ‘1979’).  Carlton Marsh, South Yorkshire by Laurence Rose Carlton Marsh, South Yorkshire by Laurence Rose The willow tit has not always been associated with such places; that is, the remnants of lost industry, although it has always inhabited wet, wooded areas rich in insects and a supply of half-rotten tree trunks in which to excavate a nest. ‘Post industrial’ is human speak for what a willow tit might call ‘that’ll do nicely’. Speculating on what a willow tit might actually be saying when he (the males do the singing) says Zi-Zi Taah Taah Taah is the subject of poem number 6 – ‘The Song of the Willow Tit’  Willow tit by Laurence Rose Willow tit by Laurence Rose The willow tit has suffered a reduction in its numbers in Britain of 94% since 1995, and a 50% contraction it its range. As we walked along a former railway, raised above the surrounding marsh, Pete Wall and Sophie Pinder of the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust explained that the wetland was excavated only a few years ago, almost instantly bringing a lushness and natural diversity to the area. Under a national species recovery programme called Back from the Brink, Sophie is part of a local team responsible for willow tit habitat management in the Dearne Valley. She is one of over thirty project officers dedicated to restoring the fortunes of 200 of England’s highest conservation priorities, from the pine marten to the narrow-headed ant. The first reed warblers of the year provided a sonic backdrop with their rhythmic rasping song; blackcaps’ mellow but tuneless warble, and chiffchaffs spiky pulse completed the accompaniment to Steve’s nine readings. Inspired as they are by one small bird, nevertheless they riff on subjects as diverse as the former coalfields’ heroin problem, the evils of capitalism, and Plenty Coup, chief of the Crow nation who wore a chickadee (the North American version of the willow tit) plaited into his hair. The willow tit, appropriately enough, contributed its silence, as unfortunately did Ted Hughes’s swifts, making us wait a few more days for confirmation that the globe’s still working. Zi-Zi Taah Taah Taah is published by Wild West Press, an imprint of the Ted Hughes Project (South Yorkshire) Back from the Brink is a programme run by this partnership of eight conservation organisations and nine main funders. Under the programme willow tit work is carried out by the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust and the RSPB. As Terry Jackson’s petition tips over the 180,000 mark, and a breakfast TV debate of sorts* exposes the issue to yet more people, it may be time to ask – how much does it matter whether or not the Oxford University Press restore the lost naturewords to the Oxford Junior Dictionary?

This morning’s ITV debate pitched two opposing views, one of which has been well covered on this website. The other took a version of the OUP line that the Dictionary is a product of a rigorous analysis and is a reflection of language as used today, not as we might like it. It was also pointed out that there is a wealth of other books – including many published by OUP – that are designed to excite children with the world, and words, of nature. Another point that is often made, but not this morning, is that this is, in any case, old news. And not just because NATURAL LIGHT first started campaigning on it over two years ago, but because the controversial removal of dozens of nature words actually took place in 2007. And ten years on, we are learning something else about language. Some of the cool new words that went in to replace otter, conker, bluebell and so many others, are already on the wane. Kids may have been endlessly chatting about chatrooms and picking BlackBerries over iPhones back in 2007, but isn’t it time to start weeding out some of those old fashioned words and replacing them with a few that simply refuse to die, like, say, otter, bluebell, conker? It has even been suggested to me that the Oxford Junior Dictionary is doing nature a service as it is, by shocking parents and teachers into realising just how disconnected families have become – from nature, and, thanks to technology and its fickle lexis, from each other. Perhaps adults should buy the OJD for themselves to use as a barometer of change to come. Either way, Terry’s petition now has its own life, as a measure of opinion and concern. In the same way that Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris’s The Lost Words exists entirely independently of its foster-parent, if the OJD can be so described, and spreads the joy of words and nature better than the OJD ever could, if the petition fails to elicit the right response from OUP, it is nonetheless doing essential work. Please sign. *starts 42 minutes in, available for 1 week Petition to restore #naturewords takes off

Watlington-based artist Terry Jackson has taken up the #naturewords cause by starting a petition to the Oxford University Press, for the restoration of some of the 100+ nature-related words removed from its Oxford Junior Dictionary. Regular readers will need no introduction to this controversy, which was first highlighted on these pages in 2015. Please sign her petition!

World Premiere, 25 November 2017, Manchester photo: Ian Phillips-McLaren photo: Ian Phillips-McLaren Two years ago I interviewed Arlene Sierra for this blog, ahead of a BBC Proms concert featuring her Butterflies Remember a Mountain. It is inspired by the annual mass migration of monarch butterflies from Canada to Mexico: each delicate insect making its infinitesimal contribution to the shimmering swarm; an unchanging annual cycle millions of years old; the sheer unimaginability of the scale of the endeavour, and a mysterious kink in the migration route are the source material for an intricate piece for piano trio. Premiered on Saturday, Sierra’s Nature Symphony is another example of her fascination with the natural world and the first of its three movements draws directly from the earlier work. Set in a fast 5/4 time the rhythmic drive of the earlier trio is maintained, while continually reusing and developing its material, and using the larger forces of the orchestra to introduce minute detailing into the texture. This gives a sense of a stream (of migrating butterflies) moving inexorably forward, but in such a swarm that the whole presents an image in stasis, until suddenly they are at their destination, the Butterfly Mountain that gives the movement its name. There is a satisfying symmetry in the overall shape of Nature Symphony: the third movement, Bee Rebellion, matches the first in rhythmic energy, and is in a similar tempo, but in 3/4 time seems busier. The pulse is destabilised by an insistent but irregular undertow of plucked double basses, while the violins and winds share a dialogue comprising short phrases that develop imperceptibly through the movement. Likening the life of the hive with elements of game theory - another favourite influence - Sierra creates a sense of frenetic but ultimately fruitless activity, and the movement ends with a sudden percussive crescendo and silence, a reminder of the colony collapse that bees are increasingly prone to, perhaps. In the middle is a movement, titled The Black Place (after O'Keeffe), that is contrastingly song-like, with a long, slow melody shaped by fragments passed between horn, cor anglais and piccolo, and on through the orchestra, accompanied by long, held notes in the low strings. The rhythmic element is again there, but as a quiet, irregular pulse of plucked strings, harp and marimba, later taken up by piano, timpani and low brass. Inspired by Georgia O'Keeffe's paintings of the austere landscapes of New Mexico, the sharing out of these rhythmic, melodic and harmonic ingredients leads to a musical landscape whose tints, rather than colours, are constantly shifting. "a personal sense of urgency" Bisti Badlands, New Mexico, close to O'Keeffe's 'Black Place' photo: John Fowler via Wikipedia Bisti Badlands, New Mexico, close to O'Keeffe's 'Black Place' photo: John Fowler via Wikipedia This middle movement is a reminder of the composer’s concern at the fragility of nature: O'Keeffe's 'Black Place' - the Bisti Badlands - is under threat from fracking. The movement borrows melodic figures from Sierra's own 2008 setting of Hearing Things, a passionately environmentalist poem by Catherine Carter. In a recent interview Arlene Sierra told Rhinegold’s Katy Wright ‘I don’t see how anyone living today can fail to realise the urgency of what is going on with the natural world and what we human beings are doing to change things. I have a little boy now, who’s five, and I’m so conscious of how different the environment is from when I was a child. It’s a personal sense of urgency.’ Nature Symphony was performed by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra at Manchester's Bridgewater Hall, conducted by Ludovic Morlot. The concert, which includes Bartók's 1st Piano Concerto and Dvořák's 8th Symphony, will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 at 7.30pm on 1 December.

Re-Wilding Nature Words: 16th - 20th October 2017 @ Therfield First School, Hertfordshire. A guest blog by Alix Marschani In the space of five minutes outside my classroom, we raced across the field, past the WILLOW and the HOLLY and found a POPPY in BLOOM. Four DELETED nature words from the Oxford Junior Dictionary re-found by the children of Therfield School. Our purpose was to find as many of these DELETED nature words to kick start our Re-Wilding Nature Words week. Above is a photo taken by a child of the poppy which poignantly is framed by a wire fence, originally marking the perimeter of the school field, interpreted by the children as ‘a jail’ ‘where the deleted words went’. ‘Save our words from jail!’ they shouted spontaneously as we later filled a flip chart of possible slogans to use for our Demo posters. The idea for this Nature Word Demo originated from my reading of the Lost Words in newspaper reports. As an educator of young children, I was alarmed that a venerable institution such as Oxford University Press should see fit to remove nature words from a much-used school dictionary without informing the public, and more importantly, the new words reflected only technological, celebrity and virtual-world activity, apparently more important than the natural world all around us. Newly included words such as chatroom, creep, MP3 player need a place in a dictionary BUT not at the expense of GOLDFISH, SPANIEL and CONKER! This is no longer a dictionary but a faddish list of words presented to a solitary child, I thought, ignoring the fact that we live on and are dependent upon a living planet, filled with birds, animals and plants we want to look after, and therefore need the spellings! After all, you cannot delete words when the object exists! This indignation was felt by the staff and children at school, especially as we have worked hard to develop a notion of the child as countryside citizen responsible for the local environment. We put our idea for a demonstration to the children – no hesitation there. We agreed as teachers that to save these words we needed to use them. If children did not know the meanings, then we had to learn these and use them. And this is a summary of what we did:

In conclusion: this work to re-kindle and re-find the Lost Words will carry on because the response has been supportive: parents are dismayed, teachers worried over the predominance of virtual worlds as refuge for children when internet safety is a daily concern. Importantly, the virtual and technological must live alongside the natural and we agree as a school there is space for both. GIVE US OUR WORDS BACK!

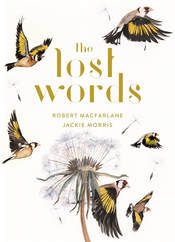

From Compton Verney to Countryfile, we're all celebrating #naturewords The former mansion house and grounds at Compton Verney, Warwickshire is the place to go for a quick lesson in how to lay on an art exhibition. Critic Waldemar Januszczak described this summer’s Op Art project as “a dazzling exhibition that sets the standard for how all shows should be done”. So, apart from the fact that their latest exhibition is all about #naturewords, I had good reason to look forward to my first visit there last night. I was not disappointed. Jackie Morris’s paintings for The Lost Words, her stunning joint venture with writer Robert Macfarlane, are presented alongside Macfarlane’s acrostic word-spells, as he calls them, each celebrating one of twenty names for everyday wild animals and plants. The story of these lost words has been told on this blog over the last three years.

Jackie Morris’s paintings for The Lost Words will be on display at Compton Verney, Warwickshire from 21 Oct to 17 Dec (except Mondays) 11am – 5pm

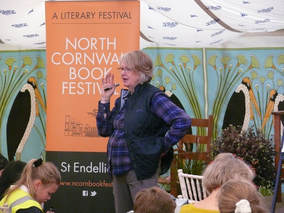

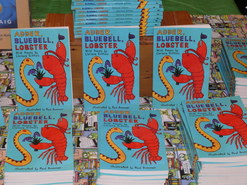

Countryfile’s edition from Cornwall will be broadcast on 22 October, BBC1 at 18:15, featuring poet Chrissie Gittins's celebration of nature words, and available on iPlayer afterwards. Her Adder, Bluebell, Lobster is published by Otter-Barry Books The Lost Words was published by Hamish Hamilton on 5 October.

On Friday, in a field near St. Endellion in Cornwall, I found myself mic’d up for a conversation with Margherita Taylor of the BBC’s rural magazine programme Countryfile. Shortly afterwards the poet Chrissie Gittins and a dozen children arrived for a nature-and-naturewords safari. Chrissie read from Adder, Bluebell, Lobster, her collection of 40 children’s poems, each celebrating a lost nature word that had been deleted from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. Then children from St. Kew, St. Minver, Nanstallon, Padstow and Blisland primary schools wrote a poem together, based on their real, direct experiences of nature.

As I was heading to the North Cornwall Book Festival and Countryfile, in Foyles Bookshop in London Robert Macfarlane and Jackie Morris were launching their own sumptuous treatment of the same subject – The Lost Words. In this review by author Katharine Norbury, it is described as “a book of spells rather than poems, exquisitely illustrated by Morris [in which] Macfarlane gently, firmly and meticulously restores the missing words.” It is almost three years since the writer Mark Cocker and I launched the #naturewords campaign, and it feels like a small October Revolution.

In a recent article, Macfarlane summarises some striking research in which a Cambridge-based team made a set of 100 picture cards, each showing a common species of British wildlife. They also made a set of 100 cards showing a “common species” of Pokémon character. Children aged eight and over were substantially better, the researchers found, at identifying Pokémon “species” than “organisms such as oak trees or badgers”: around 80% accuracy for Pokémon, but less than 50% for real species. Jackie Morris at work: words by Robert Macfarlane, set and performed by Kerry Andrew

The research showed that young children have tremendous capacity for learning about creatures -real or imaginary - but are presently more inspired by “synthetic subjects” than by living creatures. In a break from the usual dispassion of the scientist, they ponder on the fact that “we love what we know … What is the extinction of the condor to a child who has never seen a wren”?

Blogging here In August I responded – positively – to Guardian columnist George Monbiot’s call for poets to weave their word-magic to find a new vocabulary for conservation and the environment, we conservationists having been part of the problem with our alienating technocratic language. Gittins, Macfarlane and Morris are deploying their artistry in an even more fundamental way, to restore #naturewords to the mouths, and the mind’s eyes, of children.

Jackie Morris’s paintings for The Lost Words will be on display at Compton Verney, Warwickshire from 21 Oct to 17 Dec (except Mondays) 11am – 5pm

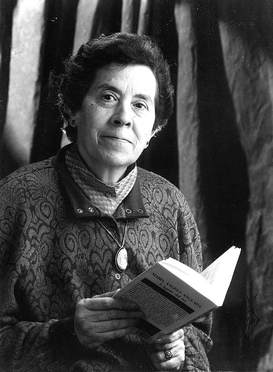

Countryfile’s edition from Cornwall will be broadcast on 22 October, BBC1 at 18:15 The Lost Words was published by Hamish Hamilton on 5 October. Adder, Bluebell, Lobster is published by Otter-Barry Books Monbiot on the language of the environment George Monbiot’s recent Guardian article on environmental language should be required reading for anyone in my profession. In recent years, a number of authors, most notably Robert Macfarlane, have catalogued our deepening nature-illiteracy. They have linked this back to our growing disconnection from nature, and forward to a future inability to respond to the needs of the natural world, due to our inability to articulate them. Monbiot has now spoken a painful truth – that scientists and environmentalists must shoulder a significant share of the blame. He points out that the language we use is cold and alienating – words like “reserve” (as he says, think of what we mean when we use that word about a person) or “sites of special scientific interest”. For the latter, he suggests “places of natural wonder” is a better reflection of what people really seek when they visit them. Monbiot goes further: not only is the language of environmentalism alienating, but it leads directly to a shift in thinking about our relationship with the natural world. He hates terms like “natural capital” and “ecosystem services”, because they ‘[inform] us that nature is subordinate to the human economy, and loses its value when it cannot be measured by money.’ Professional ecologists, he says, should recruit poets and amateur nature lovers to help them find the words for what they cherish. Having spent 35 years working as one of the thousands of amateur nature lovers who happen also to be professional ecologists and conservationists – and a few of whom are published poets – I find it striking how bilingual we are: one language for describing to each other our feelings and passions towards nature, another for our dispassionate analysis and advocacy to outsiders.  I spent the spring of 2016 on a writing project of my own.* I travelled north through Europe with the arrival of spring, between “places of natural wonder”. In Catalonia I discovered Maria Àngels Anglada, the novelist and poet. Anglada was also a conservationist, whether she realised it or not. Moved by the imminent destruction of the Aiguamolls wetlands, she wrote a Al Grup de Defensa dels Aiguamolls de l’Empordà. It foretells the cataclysm of the lost marshes: “Will they invade this living refuge that so many wings long for from afar? Will the bird of the north no longer find nourishing water and green retreats?” …. “Flamingoes, our friends the mallards, farewell, farewell, Kentish plover and lapwing, colourful princess of winter.”** Lines dedicated to the local campaigners who were fighting against overwhelming odds. The first drainage ditches had already been dug, and bulldozers entered the marshes. The machines found their way blocked, though, by local activists, who stood firm. Then in 1983, the leaders of the newly-autonomous region realised the political and cultural importance of preserving this vital link in an international network of refuelling points for migratory birds. Anglada rewrote her poem, a sigh of relief: “They have not destroyed this living refuge that so many wings long for from afar. Here the bird of the north finds nourishing water and green retreats.” …. “return, return, Kentish plover and lapwing, colourful princess of winter.” Anglada grew up speaking an illegal language. When the ice of repression receded, her words rebounded off the page, and the words she chose to use were those of nature. Olivier Messiaen was a composer whose works were inspired by the birds he, and sixty years later I, encountered on the coast near Banyuls. He wrote his first significant birdsong-inspired piece, Quartet for the End of Time, in Stalag VIII-A prisoner of war camp in Görlitz (now Zgorzelec, Poland). For both Anglada and Messiaen, wildlife symbolised freedom and identity and their works mined deep reserves of personal and cultural connectedness to nature.  Long-tailed duck by Minna Pyykkö Long-tailed duck by Minna Pyykkö In Finland I discussed the epic poem Kalevala with Minna Pyykkö, the face and voice of Finnish nature on television and radio, and an artist who has created many works inspired by Kalevala. As epics go, it is relatively recent, completed in 1849 by Elias Lönnrot, a physician who used his spare time to collect and compile the ancient oral folk tales and myths of the Finnish people. “Birds play a big role in Kalevala”, Minna told me. “They are companions to people, they whisper advice, they tease, they lift and carry tired travellers, they attack and fight with people. They also feel cold in winter and are happy when spring comes.” When the original poems were spoken, the Earth was believed to be flat. At the edges of Earth was Lintukoto, ‘the home of the birds’, a warm region in which birds lived during the winter. The Milky Way is Linnunrata, ‘the path of the birds’, the route the birds took on their journeys to Lintukoto and back. In modern Finnish, lintukoto means a safe haven, an imaginary happy, warm and peaceful paradise. Lönnrot’s poetry inspired Sibelius to write the music that would in turn inspire the creation of independent Finland exactly a hundred years ago. The natural world depicted in words and music, whether real or mythic, was an inextricable part of an emerging national identity. As George Monbiot says, ‘we are blessed with a wealth of nature and a wealth of language. Let us bring them together and use one to defend the other.’ *The Long Spring will be published by Bloomsbury in March 2018

**Very little of Anglada’s work has been translated from Catalan into English. I am grateful to the poet’s daughters Mariona and Rosa Geli Anglada who kindly gave me permission to quote and translate her work for my book, and who, along with their aunt, the poet’s sister Enriqueta Anglada d’Abadal, commented on and improved my efforts. |

WelcomeFollow us on

Facebook and Twitter Email us Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|