A conversation with Kathy Hinde Piano Migrations Piano Migrations

It is night. The inside of an old upright piano hangs in a tree. Film footage of birds is projected onto it and their wing beats generate a continually evolving musical score. Their movement is registered by a computer that responds by activating an array of tiny motors. These tap the strings at the very spot where the birds’ shadows fall. It is as if the birds themselves were creating the delicate music that emerges.

This is Piano Migrations, an installation by Kathy Hinde, one of four artists creating For the Birds a spectacular night-time trail of light, sound and sculpture at the RSPB’s Ynys-hir reserve from 2-5 October. Using LED and small speaker technology the artists are pioneering a high impact low energy spectacle. A thousand lights will wind their way through the landscape, leading into a unique spectacle of reflections and artistic interpretations on the life of birds.  photo: Joe Clarke photo: Joe Clarke

I managed to catch Kathy during a brief stop-over at her Bristol studio, fresh from the 90dB Festival in Rome and soon to head off to Wales with a version of Piano Migrations and assorted other bird-related artworks. “I’m surrounded by weird machines” was her slightly breathless greeting to my phone call.

I wanted to hear more about For the Birds. “It was Jony Easterby’s idea. He lives near Machynlleth and knows the reserve really well.” Easterby brought a number of regular collaborators together – Esther Tew, Mark Anderson and Kathy, to co-create a celebration of birds. “We are all artists who work a lot outdoors, in the midst of nature” explains Kathy. “We are installing about 26 artworks along a two-kilometre walk. We’ve worked together for a few years and know instinctively how our works will complement each other. We’ll be putting the trail together over about ten days and our walk-throughs will enable us all to refine each other’s contribution.” As for Kathy, her input revolves around the recurring themes of her work: the mapping of migratory routes, the relationship between man and technology and the effects of environmental change on nature. Piano Migrations is a characteristic fusion of natural processes, low-tech and high tech. “It changes all the time. Wherever I take it I ask them to find me a ‘new’ broken piano so the sounds are always different. And I love it when, as recently in Bavaria, they re-use the piano frame in an entirely different artwork afterwards.” Using software developed by her partner Matthew Olden, Kathy experiments with different films of bird flight to create new versions. “The first version used film I shot of house martins on telegraph wires. It looked like music on a stave and that’s how the idea came to me. I like to create systems that have their own behaviour – I compose by setting up the system but the actual music comes from the behaviours I can’t control. The original house martin version of Piano Migrations is completely different to using film of cranes, which produce a much more graceful rhythmic pattern.” I love the whole idea of migration, and there being no borders. There are lots of lovely metaphors  Origami cranes Origami cranes

I’ve noticed that cranes seem to feature a lot in her work, and I ask which came first, an interest in birds, or did that emerge through her art?

“I always spent a lot of time outdoors as a child, always in the woods. But really my interest in birds has grown around my artistic practice.” And what is it with cranes? “We made origami cranes at school and I loved it, I’ve been doing it ever since, making them flap their wings and everything. Then in 2010 I spent sixteen hours in a hide in Hornborga, Sweden, with real cranes all around doing their dancing displays a few feet away from me. One of my installations at Ynys-hir will be stainless steel ‘origami’ cranes with motors to make them move and lit up with special lighting.” “I love the whole idea of migration, and there being no borders. There are lots of lovely metaphors.” Kathy then reveals that her great-grandmother was a migrant - arriving in Britain from Lithuania in 1901. “And my grandmother sold pianos in Wigan, so these connections mean a lot to me.” I want people thinking about the sights and sounds of nature in different ways  Bird-imitating machine Bird-imitating machine

So what other weird machines will she be taking to Wales? “I’m working on a bird imitating machine using Swanee whistles whose tails are controlled by computer. I’m composing a piece for this machine but the prototype still needs improvement.”

It is only late in the conversation that I realise the Ynys-hir installation is for visiting after dark. “Ynys-hir has these amazing vistas over the estuary but we want to bring it to life at night, and create a different feel. “I want people thinking about the sights and sounds of nature in different ways...” “You seem to want to magnify everyday experiences of nature” I suggest. “Exactly, that’s a good way of putting it. My motivation is to imbue a desire to care for the environment, but it’s implicit in the work that I make, it’s not something that I preach. People have to get there themselves.”  Ynys-hir RSPB reserve Ynys-hir RSPB reserve

For the Birds, a nighttime journey into a wild avian landscape. New Site-specific works by sound and visual artists Jony Easterby, Mark Anderson, Kathy Hinde and Esther Tew at Ynys-hir RSPB reserve, Wales

2-5 October, Ynys-Hir, nr Machynlleth, SY20 8TB NATURAL LIGHT and the Cheltenham Literature Festival have tickets to give away for two great events! Click the button to go to our tickets page. The festival opens on Friday 3rd October when we are offering a free pair of tickets for The Great Outdoors Writers Will Atkins (The Moor) and John Lewis-Stempel (Meadowland) and natural navigator Tristan Gooley (The Walker’s Guide to Outdoor Clues and Signs) discuss our relationship with the British countryside. Another free pair of tickets is on offer on Friday 10th October to hear top nature writers (l. to r. below) Simon Barnes (Ten Million Aliens), Richard Girling (The Hunt for the Golden Mole) and Richard Kerridge (Cold Blood) journey around the animal kingdom, covering biodiversity, conservation and the relationship between man and beast in Nature’s Wonders. Cheltenham Literature Festival 3-12 October For ten days every Autumn Cheltenham welcomes over 600 writers, actors, politicians, poets and leading opinion formers to help celebrate the joy of the written word. Established in 1949, The Times and Sunday Times Cheltenham Literature Festival is one of oldest literary events in the world. “Nature has always been a boundless source of inspiration for writers over the centuries" says Cheltenham's Candice Pearson, "so of course we always programme a number of events about, or informed by, the natural world”. Writers and nature lovers have so much in common: both are great observers of their surroundings After just over a year, BBC Radio 4’s Tweet of the Day is already a national institution. “This year we’re delighted to be welcoming the BBC team behind Tweet of the Day to talk about their fantastic feature which gives listeners a daily dose of birdsong" says Candice. Series producer Brett Westwood and naturalist Stephen Moss explore changing lives of Britain’s birds – their songs, calls and habits. Regulars will know that NATURAL LIGHT has started Re:Tweet of the Day and we’ll be putting out a Re:Tweet Cheltenham Special on the 3rd. I asked Candice why nature is such a strong theme at Cheltenham. “Writers and nature lovers have so much in common: both are great observers of their surroundings, perceiving and drawing meaning from the countless mini dramas that take place but go unnoticed by most”. The first afternoon - 3 October - sees no fewer than three nature-inspired events. After The Great Outdoors and Tweet of the Day Canadian anthropologist, ethnobotanist and photographer Wade Davis, author of Into the Silence shares his extraordinary and inspirational stories of exploration and discovery in the Amazon Rainforest in One River. expect our view of the countryside to be challenged As always, Cheltenham will be providing a platform for debate about tough issues of our time. “Our natural environment is of course always changing and so we’ll be looking to the future as we tackle big debates, such as how we’ll feed the world in the years ahead and what repercussions this will have on the countryside.” Artists Ackroyd & Harvey, Kathleen Soriano, former Director of Exhibitions at the Royal Academy of Arts and author Andrew Brown (Art & Ecology Now), explore how contemporary artists are responding to growing ecological threats in Can Artists Change the World? on 6 October while the next day James Lovelock talks to Crispin Tickell about his new book A Rough Ride to the Future. On 11th we can expect our view of the countryside to be challenged when Guardian columnist George Monbiot gives a deeply personal talk about reconnecting with nature and challenging what he calls “ecological boredom”. Later in the day Monbiot will be joined by Nick Bostrom (Superintelligence) and Ian Goldin (The Butterfly Defect and Is the Planet Full?) to contemplate the global landscape in 2114. Poet Pascale Petit, who was interviewed by NATURAL LIGHT a couple of weeks ago is joined by Ruth Padel on 7th so we can expect two very different, but highly imaginative, expressions of a shared passion for animals. Another NATURAL LIGHT favourite, composer Harrison Birtwistle, reveals the challenges, uncertainties and rewards which have shaped his life and work, in conversation with Fiona Maddocks.

For full details of the many other green bits in this year's Cheltenham Festival, from Amazonian river life to water voles, see our What's On page.

Like millions of people, I first heard the incredible song of the Lyrebird courtesy of David Attenborough’s Life of Birds series back in 1998. Those few minutes of expert mimicry have been voted one of the most popular wildlife clips ever. This morning Sir David presented this wonderful songster on Radio 4's Tweet of the Day.

Fir0002/Flagstaffotos Fir0002/Flagstaffotos

Unsurprisingly, the lyrebird features in aboriginal Australian music, in what may be a continuous tradition lasting tens of thousands of years. Matthew Doyle, a composer and dancer of aboriginal-Irish descent, continues this tradition in a series of pieces for voice, didjeridu and percussion, issued on a CD entitled, simply, Lyrebird.

A composer who famously appropriated birdsong into many works was Olivier Messiaen, and later composers such as Harrison Birtwistle have claimed that his Messiaen’s style oiseau had a direct and lasting impact on modernists searching for more naturalistic – or at least less formal – musical structures. It is perhaps fitting that Messiaen’s last completed work should incorporate the bird widely regarded as having the most extraordinary song of them all. Éclairs sur l'au-delà… [Illuminations of the beyond…] is an orchestral piece composed in 1987–91. Messiaen visited Australia during that country's bicentennial celebrations in 1988, enabling him to use the sounds of Australian birds notated in the wild. The third of eleven movements is called L’Oiseau-lyre et la Ville-fiancée [The Lyrebird and the Bridal City]. Whereas traditional Australian music features vocal and didjeridu imitations of birds, Messiaen's works attempt to reproduce the extreme complexity of bird song through notated music. L'oiseaux-lyre et la Ville-fiancée is among his most complex, with 67 changes of tempo and a dizzying variety of motifs.

Someone who knows these birds and their songs well is the composer Edward Cowie, who was interviewed by NATURAL LIGHT a couple of weeks ago. He spent twelve years in Australia in the 1980s and 90s and describes an evening sitting at the edge of a cliff overlooking the King Valley in Victoria. “Just as the light finally dipped towards an inky darkness, several male lyrebirds began to sing in a series of interlocking but combative ensemble performances”. Cowie often contrasts himself with Messiaen: he doesn’t attempt to note, and then notate, the exact rhythms, pitches and timbres of the bird. He is more interested in natural sound as part of an overall experience of a landscape, a place, a moment.

For me, Lyre Bird Motet captures that smoky valley in Victoria wonderfully. Cowie uses rather dreamy harmonies from one part of the chorus to suggest a balmy dusk scene while the other singers, like a real evening chorus, are all (seemingly) independent soloists, bringing bursts of sound, or maybe shafts of light, into the dim, cool forest.

This morning, on Tweet of the Day, we heard how the Lyrebird – a bit like Edward Cowie - is an avid borrower of sound, listening, choosing, and replaying echos of its own immediate environment. Recently, while preparing a talk about birds and music, I ran a search for samples of lyrebird song. The best was from a captive bird in Adelaide Zoo. The lyrebird enclosure was in need of repair and a pair of local builders had been brought in. Some days later Chook, the dominant male lyrebird, gave a recital of his latest composition, based mainly on the sounds he had borrowed from the builders. In a remarkable recording we hear the hammering of a hammer, the whirr of an electric screwdriver, a power drill, and an old-fashioned hand saw cutting through a plank. We also hear one builder greeting the other and we can surmise that Chook’s neighbours included a whip-bird and a kookaburra, because we hear a perfect imitation of them both – simultaneously!

Update: Edward Cowie's Lyre Bird Motet will be part of the BBC Singers' 90th birthday celebrations next Wednesday 24th September, St. Giles Cripplegate, London 6pm.

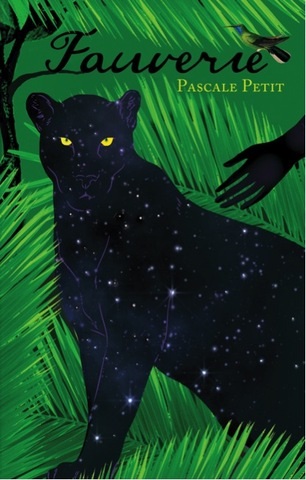

A conversation with Pascale Petitwhen I write about the natural world just for its own sake it makes me happy Passionate about the natural world, obsessive about using images from nature to paint the darker side of human nature. NATURAL LIGHT caught up with French-Welsh poet Pascale Petit ahead of the launch of her sixth collection, Fauverie. A series of launch readings begins next week in Norfolk, taking in events as diverse as London Zoo’s first ever Poetry Weekend and the Resurgence and Ecologist Festival of Wellbeing. (See What’s On for full details) Petit was taking time away from her home in London and back in her native Paris on a writing retreat, so we agreed to converse by email on this occasion. I’d read that Fauverie is inspired by the big cat house of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris and celebrates the ferocity and grace of endangered animals. But I wanted to check my understanding: whereas her fourth collection, The Treekeeper’s Tale, displays an intense feeling for nature in its own right, the new collection invokes nature metaphorically, to tackle the darker aspects of human nature. “Yes I think that’s fair. The natural world is my passion, but my subject has often been my parents and human nature. I’ve written two books about my father (The Zoo Father and Fauverie) and one about my mother (The Huntress) and I’m working on another sequence about my mother Mama Amazonica. So I guess on the one hand there’s my passion – the natural world – and on the other my obsession – to write about my strange parents.” I’m keen to know how – indeed if - Pascale separates these two very different ways of viewing nature; or is it a single, much more complex relationship? “I write intuitively and don’t analyse much as the poems come but I do know that when I write about the natural world just for its own sake it makes me happy. I also think that it’s harder for me to do that successfully. “When I write about my parents it’s not because I think anyone’s interested. As Sharon Olds has said, no one is interested really, why should they care? What I’ve tried to do with my father is to turn him into two books (he was an absent father), so I have these two books instead of him, and in them I deal with the evil things he did, and I change them by bringing in the natural world, especially animals, so that the recreated father I end up with is one I love, because he’s all these amazing animals.  photo: Rodney Jackson photo: Rodney Jackson “It is a complex relationship. I am fascinated by the primitive and ferocity. I’m very drawn to Amazonian animals in particular, though others that are fierce, such as snow leopards and North China leopards, do it for me too. How could they not? North China leopards are especially savage and hard to keep in zoos, they keep their fierce natures and snarl a lot!” Why Amazonia? “My fascination with Amazonian animals, anything Amazonian actually, the plants and peoples too, came from two trips I made in the Venezuelan Amazon in the 1990s. I went in 1993 and 1995, just two years before my father contacted me. I hadn’t heard from him for 35 years! So I visited him in Paris as he was an invalid, dying of emphysema. I took time out from those claustrophobic visits to go to the Ménagerie zoo in the Jardin des Plantes where I discovered there were many Amazonian species. So those two things – the Amazon and my father – became intertwined in my mind. I found I could only write about him through those animals. I read everything I could find about the Amazon, the flora and fauna, the landscape, its tribes, their rituals, and especially their mythologies and spiritual lives. When I started writing my second book about my father, Fauverie, I avoided going to the zoo and concentrated on Notre-Dame and the city of Paris, but I soon broke my veto and started going there more than ever, almost every day!” Aramis the black jaguar. What a fabulous creature he is!

Pascale Petit’s previous collection What the Water Gave Me: Poems After Frida Kahlo, was shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize. Reading dates for Fauverie are listed in the What’s On section and start on 19 September at the Wymondham Words Festival.

A guest blog from Michael Hatfield photo: Laurence Rose photo: Laurence Rose The RSPB Beckingham Marshes reserve on the River Trent commissioned Kerry Greenwood and the Kismet Theatre Company based in Gainsborough to create a theatrical performance to raise the profile of the site and let people know about what a great place they have on their doorstep. Marshsongs, written by local playwright Michael Hatfield is a journey through the history of the marshes. It will include scenes created by local community groups, inspired by their own visits to the site, as well as specially created visual arts, music, poetry and song. NATURAL LIGHT asked author Michael Hatfield to share his experience of the project: Meeting one with Director Kerry Greenwood. A lovely meal, followed by a comprehensive destruction of every scene, every idea. There were funny scenes, clever ideas. But Kerry clearly identified the problem- it was a generic script, exploring different time periods and various animals and situations. But it wasn't rooted in truth. She gave me one principle to follow which made all the difference "Make it specific to the place. Make it true. Go back to how you felt when you visited the marshes" When we visited the marshes, my first impression was of a big flat empty field. But as we walked around, I began to notice small things: frogs underfoot, hovering dragonflies, beautiful blue unnamed insects, lapwings flying overhead. And suddenly, I was lost in a world within our world. Here was a universe beneath our feet and over our heads. I loved the feeling that the world was shifting around me and growing wider and deeper by the second. I wanted to recapture that emotion- like falling into a microscope and feeling a tiny being in an infinite cosmos. But a play has to be about stories and people. So the research began. Local history, websites, records, talking to local people. What was the story I wanted to tell? What needed to be told? What struck me was that almost every story about the relationship between Man and Nature was about Mankind's destruction of the natural order. But here, here in Beckingham Marshes, the reverse is the case- the development of flood plains (to protect Mankind) had enabled the creation of a wetland reserve, bringing back ancient habitat and ancient animals. A true kind of symbiosis. Real progress. The next meeting with Kerry was electric. We both knew we had found the key. Real history, combined with poetry and magic would create a timeless piece of drama. Time to get to work. Daft Annie's speech reflected the way I felt that day in the marshes...

Curlews wade, mud-lovers, mud-hunters, searching, searching, spiked bills piercing the hot sticky ground. Scimitar carves the air. Worms wriggle in the air. He waddles off. Drumming, drumming, the snipe are drumming. Feathers humming. Show offs. It's the men. Always the men. Showing off. Fly high in the hand of God, then down, down to the ground. Wagtails, water pipits... The flash of yellow. Yellow hammer! Little bit of bread and no cheese. Little bit of bread and no cheese. Every song is different. Listen to the boys singing. Yellow breast and head of solid gold. Yellow hammer.  photo: Robin Booker photo: Robin Booker Then the local Performing group PACS to represent the animals, then local writers and poets to have their poems read. The second half moves into the Twentieth and twenty first century. In a swift succession of scenes we visit the Marshes in 1940, 1947, 1977, 2000 and 2007. We see the devastating impact of floods and storms over the years, and how Marsh Folk cope. And finally, a reminder of the devastating impact destruction of habitat has on the natural world. We don't want the audience to be spared the realities. And then end with a joyous celebration of the renewed Marshes as a partnership between Man and Nature. MARSH: Life is born, life ends. That’s the way of things. I don’t overcomplicate. The small things live in me, they grow. Look closely- you will see a world within the world. A daily struggle for survival. The world of the insects, the microscopic world. You need to see with new eyes. Here’s warfare, kill or be killed. Progress. Mankind builds. They make. They construct. And they call this progress. They build walls and fences, to close me in. They call this ownership. That's the plan - a show that begins in prehistory and ends in 2014, a show that is specific to the history of people and places around Beckingham- but which touches on the transcendental and universal. A combination of music, movement, drama and poetry which might just make people feel the way I did, stood in a muddy field in silence, touching hands with the infinite. Michael Hatfield Michael Hatfield is a local writer who has written adaptations of Mediaeval Mystery Plays, a seventh century Spanish drama, pantomimes, Youth Theatre plays, and song lyrics. Marshsongs will be performed on Friday and Saturday 19 and 20 September, 7.30 pm at Beckingham Village Hall, Notts and on Friday and Saturday 26 and 27 September, 7.30 pm at Gainsborough Old Hall, Lincs. Booking recommended 07756 500292

Walking, reading and writing in the Peak District Rob Bendall Rob Bendall The Peak District has inspired and informed poets for decades. Two of today's poets most inspired by the brooding fells, Jo Bell and Tony Williams join forces this Saturday afternoon to lead an inspiration-gathering walk and to share their poetry and encourage participants to gather material and share theirs. Williams's latest collection The Midlands includes many pieces inspired by the region. Williams and Bell have selected poems to share along the route, which aims to gather ideas and images for informal writing and poem-sharing at the end of the walk. See What's On for more details. Welcome......to a new occasional series that takes the subject of the morning's Radio 4 Tweet of the Day and explores music inspired by that species. This morning, Sir David Attenborough introduced us to the Australian Magpie.  It is difficult to imagine a composer taking our magpie’s song as a starting point for a piece of music, but the Australian version’s melodious song with its clearly pitched notes is celebrated by several including John Rodgers and Ross Edwards, two Australian composers who often feature bird songs in their works. British composer David Matthews describes how friends he was staying with introduced him to the song of their resident magpie. He wrote down this haunting song, hoping to use it in some way. Later he noted down three more songs, two of them distinctively melodic. The koel, a large Australian cuckoo, had just arrived for spring - and sang day and night. The pied butcherbird sings three notes on different distinct pitches. Lastly, the eastern whipbird has a crescendoing high note followed by an extraordinary, loud whip-crack. From this material Matthews wrote Aubade, for chamber orchestra. It develops the initial eight notes of of the Australian magpie’s song into a long violin melody which is later reprised on the cello. Matthews says "My recent music has become more diatonic, and I have been using folksong in some pieces, and incorporating birdsong into others. Landscape and the natural world have always been important stimuli for my music". Michael Kennedy, writing in the Sunday Telegraph in 2001 described Aubade as “an appealing essay in the honourable English tradition of short nature pieces – rather like a present-day equivalent of Delius’s First Cuckoo.” A conversation with Edward Cowie Hest Bank photo: Laurence Rose Hest Bank photo: Laurence Rose

On a cold November morning in the late 1970s a small group of us assembled on the shores of Morecambe Bay, near the village of Hest Bank. We were there to meet the high tide wader roost, a host of oystercatchers and ringed plovers, in order to net them, ring them and release them as part of a long-term research project into long distance migration.

One of my fellow ornithologists was Edward Cowie, then Associate Professor of Composition at the University of Lancaster, where I had just enrolled as an undergraduate in biology. From then until Edward’s move to take up an academic post in Australia in 1983, we would encounter each other at bird club meetings, in the field and at concerts. Our conversations were most often about birds, but sometimes about music. As for Hest Bank, it was to be the inspiration for an early but already characteristic Cowie piece – an eponymous movement from his Gesangbuch, a cycle of virtuosic choral works written for the BBC Singers. Cowie’s Hest Bank captures in sound a rippling, surging, swirling, murmuring, flowing and ebbing of vast flocks of knot, dunlin and other waders; of water, surf and flotsam; of light and of landscape. One of the things I like about being a composer is it always takes me somewhere strange

I caught up with Edward as he was preparing for a trip, with his partner, the artist Heather Cowie, to a very different wetland. They are spending the rest of September in Botswana’s Okavango Delta, where Edward will be researching new pieces with the support of a Leverhulme Emeritus fellowship. Surprisingly, it is Edward’s first visit to tropical Africa.

“One of the things I like about being a composer is it always takes me somewhere strange. I don’t know how I will react but I know it will be the whole interlocking tapestry that will impress me: the sky, the flatness, the wetness.” He knows enough about what to expect to have decided how he intends to work. One of the main outputs from the trip will be Okavango Nocturne. It will be the second in a cycle of orchestral works with the overarching title Earth Music. The first was Great Barrier Reef, commissioned by the BBC Proms and premiered there last year.

“I’ve heard that the Okavango has a very special night-time atmosphere, full of sound coming from millions of animals of all kinds. I’ll be out there listening very carefully to a habitat that can’t be seen, only heard.” Okavango Nocturne will be premiered in the 2015/16 season.

I remark that his search for some special magic in the Okavango is characteristic, something he has been doing for years in the wild places of the world. He agrees and explains that in Australia he often spent long periods alone in wild areas, contemplating and exploring nature and the sonic and visual experiences it affords. He describes an evening sitting at the edge of a cliff overlooking the King Valley in Victoria. “Just as the light finally dipped towards an inky darkness, several male lyrebirds began to sing in a series of interlocking but combative ensemble performances”. He was captivated by the sounds, but also by the whole experience: the changing light as dusk falls; tracing wisps of smoke that perforate the forest canopy, the valley landscape enclosing this world of sound and atmosphere. The result of that experience was one of his best-loved pieces, Lyre Bird Motet (2003), written for the BBC Singers. A return trip to Australia a few years ago led to a companion piece, Bell Bird Motet, premiered in 2011 by the BBC Singers at the festival Earth Music Bristol which Edward founded.

For Edward, drawing is an integral part of music composition. “I’ll be taking a manuscript book to note down the sounds that I hear, but the visual dimension is important – even in the dark. Composition is for me ‘multi-sensing’ – I draw to capture shape, form, complexity versus simplicity, colour and ‘event.’ I add real musical notes in the drawings if I need to, and then start translating it all into the music."

photo: Luca Galuzzi www.galuzzi.it photo: Luca Galuzzi www.galuzzi.it

Our conversation runs like a river in spate, with unexpected turns and splashes. Suddenly we are discussing the recent discovery of the phenomenal song repertoire of the spiny lobster. It turns out Edward is working on an Australian Broadcasting Corporation radio series called Singing Planet. It’s a natural history of song “from crustaceans to the contemporary chorus.”

We return to the calmer waters of the Okavango and Edward reveals plans for another Botswana project - researching big cats for a piece for clarinet quintet. “I recently got to know [British clarinettist] Julian Bliss and have been bowled over by his playing – it’s great to hear someone so young display a totally unmediated love of sound” he enthuses, "and it turns out Julian is seriously keen on wildlife. I’m writing a clarinet quintet for him, so I asked him what subject he’d like me to focus on and he immediately said ‘big cats’. So the piece will be called Big Cats. “I have millions of reasons to compose music, and they are mainly, if not totally, found within the way the natural world works.” Laurence Rose

Cheltenham Literature Festival (3-12 October) tickets go on general sale today, and a glance at the programme reveals a wide range of authors, works and discussion fora on environmental, countryside and nature subjects. NATURAL LIGHT will be giving a full preview later in September. In the meantime, check the What's On section for a summary of Cheltenham's Green bits. |

WelcomeFollow us on

Facebook and Twitter Email us Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed