A conversation with Pascale Petit

when I write about the natural world just for its own sake it makes me happy

(See What’s On for full details)

Petit was taking time away from her home in London and back in her native Paris on a writing retreat, so we agreed to converse by email on this occasion. I’d read that Fauverie is inspired by the big cat house of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris and celebrates the ferocity and grace of endangered animals. But I wanted to check my understanding: whereas her fourth collection, The Treekeeper’s Tale, displays an intense feeling for nature in its own right, the new collection invokes nature metaphorically, to tackle the darker aspects of human nature.

I’m keen to know how – indeed if - Pascale separates these two very different ways of viewing nature; or is it a single, much more complex relationship?

“I write intuitively and don’t analyse much as the poems come but I do know that when I write about the natural world just for its own sake it makes me happy. I also think that it’s harder for me to do that successfully.

“When I write about my parents it’s not because I think anyone’s interested. As Sharon Olds has said, no one is interested really, why should they care? What I’ve tried to do with my father is to turn him into two books (he was an absent father), so I have these two books instead of him, and in them I deal with the evil things he did, and I change them by bringing in the natural world, especially animals, so that the recreated father I end up with is one I love, because he’s all these amazing animals.

photo: Rodney Jackson

photo: Rodney Jackson Why Amazonia?

“My fascination with Amazonian animals, anything Amazonian actually, the plants and peoples too, came from two trips I made in the Venezuelan Amazon in the 1990s. I went in 1993 and 1995, just two years before my father contacted me. I hadn’t heard from him for 35 years! So I visited him in Paris as he was an invalid, dying of emphysema. I took time out from those claustrophobic visits to go to the Ménagerie zoo in the Jardin des Plantes where I discovered there were many Amazonian species. So those two things – the Amazon and my father – became intertwined in my mind. I found I could only write about him through those animals. I read everything I could find about the Amazon, the flora and fauna, the landscape, its tribes, their rituals, and especially their mythologies and spiritual lives. When I started writing my second book about my father, Fauverie, I avoided going to the zoo and concentrated on Notre-Dame and the city of Paris, but I soon broke my veto and started going there more than ever, almost every day!”

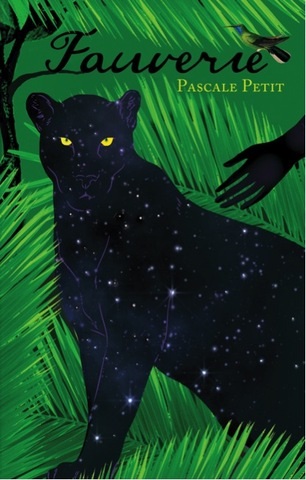

Aramis the black jaguar. What a fabulous creature he is!

| Tell me about Aramis. “There are several poems in Fauverie about Aramis the black jaguar. What a fabulous creature he is! In some of them he is also my father and in some he is just himself. He may therefore be bad sometimes, but he is always exonerated because of his magical spirit. Which I hope means my father is also redeemed in those poems.” This all sounds very different to The Treekeeper’s Tale, I suggest. “The Treekeeper’s Tale is different. I wanted to focus on the natural world. I’m not sure those poems succeed. Or perhaps they lack the intensity of the poems where the central concern is human nature. There’s a sequence in the book about the coast redwoods in California. I’d gone there a few times and was so wowed by those trees. But I don’t think I did them justice.” Laurence Rose |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed