The sounds of the natural world are orchestrated in a similar way to classical compositions, and are as emotionally moving. This is the message from three people who share a mission to bring these sounds and the world of music together. I went along to the Barbican in London yesterday to hear a public conversation between soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause, composer Richard Blackford and BAFTA-winning sound recordist and sound artist, Chris Watson.

Krause’s book The Great Animal Orchestra coined three terms to demarcate the sounds that surround our everyday lives, according the whether they are human, animal or geological in origin. He began by showing graphically how insects, birds and other songsters avoid using the bandwidths that are dominated by what he calls the geophony – the sounds created by the earth itself, of rivers, wind and the like. The biophony of animal sounds is itself divided into clear strata so that each species group makes sounds at the pitches avoided by everyone else. Put this onto a sonograph and the similarity with a musical score is striking. Anything else – the sounds of cities, industry, transport for example – forms the anthropophony.

Krause’s book The Great Animal Orchestra coined three terms to demarcate the sounds that surround our everyday lives, according the whether they are human, animal or geological in origin. He began by showing graphically how insects, birds and other songsters avoid using the bandwidths that are dominated by what he calls the geophony – the sounds created by the earth itself, of rivers, wind and the like. The biophony of animal sounds is itself divided into clear strata so that each species group makes sounds at the pitches avoided by everyone else. Put this onto a sonograph and the similarity with a musical score is striking. Anything else – the sounds of cities, industry, transport for example – forms the anthropophony.

Your eyes show you want you think you need to see; your ears tell you the truth

| Bernie Krause has used soundscapes, and their visual representation as sonographs, to demonstrate clearly the impoverishment of a badly-managed forest. Before-and-after photos at Lincoln Meadow, California, showed a forest that looked as rich and beautiful after selective logging as before; but sound recordings and the sonographs they generated showed clearly how bird and insect life had largely disappeared. "Humans live in a visual world" he said, "so our eyes show us what we think we need to see to survive; but our ears tell the truth." | |

Krause and Oxford-based composer Richard Blackford have taken the idea of species' occupying different sonic niches and collaborated on a new work for orchestra and recorded soundscapes, also entitled The Great Animal Orchestra. This work is premiered at the Cheltenham Festival on 12 July, and broadcast live on BBC Radio 3. We were given a brief preview of the opening, with a projected sonograph to follow rather than a score. The first few moments take the natural sounds of the rainforest and contrives through filtering technology to have this start in the highest register, with progressively deeper sounds allowed back in according to a mathematical-looking curve; all of which was clear to follow on the screen. Then, after a few seconds of full natural orchestra, the human orchestra emerges from the complex rainforest soundscape, via a C-sharp on which the gibbon’s dawn song ends, to be taken up by the violins. The five-movement work includes a part for a heart-rending call from a male beaver whose family had been violently killed by fishermen; the original recording was played to a visibly shocked audience.

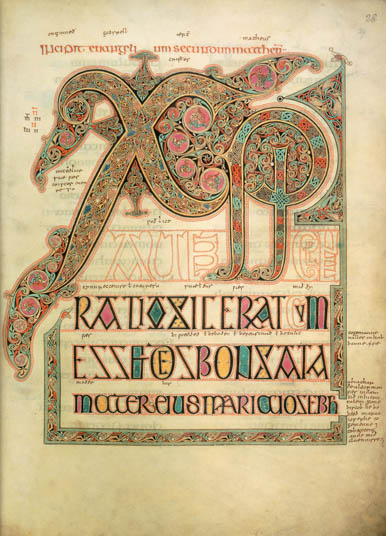

Chris Watson - Northumberland based globe-trotting sounds man for the likes of David Attenborough - has been reflecting lately on the sounds that would have surrounded Eadfrith as he made his fabulous illuminations in the Lindisfarne Gospels. It is hardly surprising, he says, that the island's creatures such as eider ducks and grey seals should feature in the manuscript. The human song-like sounds they make would have been unpolluted by the machines and traffic that were over a thousand years into the future. He played his own recordings to make the point, and conjured a picture of grey seals singing in the misty distance, originating the many legends of half-human sea-creatures.

Watson’s credentials are second-to-none; the founder member of experimental music band Cabaret Voltaire went on to become a sound recordist for the RSPB Film Unit before his freelance work took him several times around the world to produce unique, and award-winning, material for ground-breaking BBC series such as Life of Birds and Frozen Planet. His sound art has been installed in dozens of public places and his soundscape recordings have been released in a number of CDs including In St.Cuthbert's Time, using material from his studies of the sounds of Lindisfarne.

Chris took his audience on a dizzying sonic world tour to sample some of the fruits of his insatiable curiosity, from the whales calling their kin across hundreds of miles of ocean to assemble in the Dominican Republic, to Japan, where the suzumuchi cricket is revered for the purity of its autumn note. A touching song to the mountains from a Sami elder in Norway was answered, exactly on the beat I noticed, in a haunting echo. Finally, the lights were dimmed as he played us the pre-dawn chorus from his own patch, the Northumberland moors, resonating to an orchestra of drumming snipe, bubbling curlew, skirling lapwings and keening golden plovers.

Laurence Rose

Chris Watson - Northumberland based globe-trotting sounds man for the likes of David Attenborough - has been reflecting lately on the sounds that would have surrounded Eadfrith as he made his fabulous illuminations in the Lindisfarne Gospels. It is hardly surprising, he says, that the island's creatures such as eider ducks and grey seals should feature in the manuscript. The human song-like sounds they make would have been unpolluted by the machines and traffic that were over a thousand years into the future. He played his own recordings to make the point, and conjured a picture of grey seals singing in the misty distance, originating the many legends of half-human sea-creatures.

Watson’s credentials are second-to-none; the founder member of experimental music band Cabaret Voltaire went on to become a sound recordist for the RSPB Film Unit before his freelance work took him several times around the world to produce unique, and award-winning, material for ground-breaking BBC series such as Life of Birds and Frozen Planet. His sound art has been installed in dozens of public places and his soundscape recordings have been released in a number of CDs including In St.Cuthbert's Time, using material from his studies of the sounds of Lindisfarne.

Chris took his audience on a dizzying sonic world tour to sample some of the fruits of his insatiable curiosity, from the whales calling their kin across hundreds of miles of ocean to assemble in the Dominican Republic, to Japan, where the suzumuchi cricket is revered for the purity of its autumn note. A touching song to the mountains from a Sami elder in Norway was answered, exactly on the beat I noticed, in a haunting echo. Finally, the lights were dimmed as he played us the pre-dawn chorus from his own patch, the Northumberland moors, resonating to an orchestra of drumming snipe, bubbling curlew, skirling lapwings and keening golden plovers.

Laurence Rose

RSS Feed

RSS Feed